When I first started getting into music, I was all about the piano. But then I started listening to new-wave bands like Depeche Mode, Erasure, and Duran Duran and I was like, “Whoa, how did they make those sounds?!”

That’s when I decided to get my first synthesizer in high school and start tinkering with it.

It was an analog synthesizer with all these cool knobs and waveforms, including this oscillator section with switches for sine, triangle, and square. I had no clue what any of it meant, but I could totally feel and hear the effects.

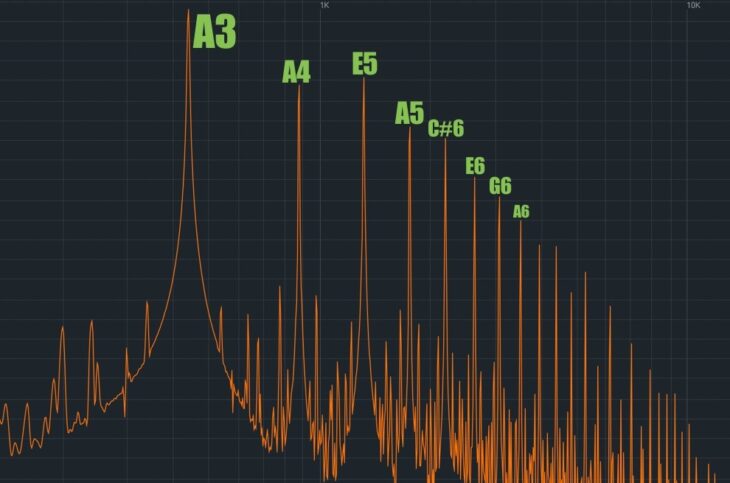

Later on, when I was studying music at Berklee, I learned that everything I was hearing really came down to the basics of fundamentals and overtones. Whether you’re plucking a string on a guitar, playing a piano note, or triggering an oscillator on a synth, it all comes back to harmonics.

Fundamentals vs. Overtones

Alright, so here’s the deal with fundamentals and overtones. Basically, every wave can be broken down into fundamentals and overtones (except for the basic sine wave, of course). Sine waves are fundamental only, without any overtones or harmonics.

Think of the 808 kick in hip-hop and trap music. It’s a classic example of a sine wave. One of the reasons it cuts through the mix so well is because it’s a pure fundamental frequency.

The fundamental frequency is the loudest and first sonic manifestation of a waveform. It’s the actual note that you perceive as the pitch. On a sine wave, it’s smooth and quite deep if it’s on the lower end of the spectrum.

That’s why a lot of synth bass and drum machine kick drum sounds are based on sine waves.

When you get into more complex waves, like square waves or triangle waves, you start hearing brighter tones. These are just the constant multiplication of the fundamental frequency going higher and higher up the range.

In the case of square and triangle waves, they’re mostly odd harmonics, with the Triangle wave having fewer overtones, thus giving it a smoother, hollow tone, almost flute-like. In contrast, a sawtooth wave contains both odd and even harmonics, making it the brightest and buzziest sounding.

That’s why many synthesizers have filters after the oscillator section, to tone down the brightness caused by exciting the oscillator waves, especially in the higher frequencies. Most synthesizer filters, like on the Minimoog, are low-pass filters, which darken the higher overtones and harmonics so that the sound isn’t too harsh.

When you pluck a guitar string or a piano string, your ear mostly catches the fundamental, but the overtones sustain long after.

For example, if you play a C1 base frequency, the fundamental would be at 65 Hz, while the overtones would be a multiplication of that. So the first harmonic would be at 130 Hz (2 x 65Hz), or an octave higher. The third harmonic would be at 195 Hz (3 x 65Hz), which is actually an octave and a fifth higher, and so on.

In many ways, any note other than a sine wave is harmonically a chord in itself. We just don’t perceive it that way because the fundamental is much louder than the rest of the overtones.

Overtones and Distortion Types in Music

When it comes to music recording, overtone harmonics can be heard more clearly when the sound is heavily distorted or compressed through musical equipment. For instance, the blues guitar has a sweet and textured sound compared to playing a dry guitar without an amplifier. Why is that? It’s due to the even-order harmonics produced by overdriven tubes.

Another widely used form of harmonic distortion in music is recording to magnetic tape. Tape distortion accentuates third-order harmonics, which are richer because they are not pure octaves.

The closer overtones produce a much sweeter and richer sound that is easy on the ears. Richer harmonics are also called in-harmonics or partials because they fall in between even and odd overtones.

Some studio equipment, like the Empirical Labs Distressor, adds a little bit of THD (Total Harmonic Distortion), which accentuates the partials while leveling out volume peaks in the music. It even has dedicated buttons to choose between second-order harmonics that mimic the effects of tubes and transistors, and third-order harmonics to mimic tape.

It’s a legendary piece of gear found in most studios and has been used on practically every record for the past three decades.

Final Thoughts

Summing it up: the fundamentals plus overtones, also known as the harmonic series, are not only present in music but also in everything you hear. But here’s my take on it – music and music recording have made us more aware of this phenomenon beyond just a scientific explanation. We perceive it on an instinctual level.

That’s why plug-in companies (like Universal Audio) use software modeling to analyze the non-linear harmonic properties of tubes and tape machines. They are trying to replicate the way iconic pieces of audio equipment worked.

Even if you’re not a musician, you have to admit that you recognize the “warm” and “rich” sound of harmonically complex recordings or a large orchestra playing together, right? I mean, that’s why people describe something beautiful sounding as “warm” and “rich” in the first place.

The richness comes from all the harmonics being amplified in your face, whether it’s by 80 players getting together in a confined space or a beautifully saturated recording.

And that’s why music is so special and emotional. The magic lies in what you feel but don’t necessarily hear.